|

PASTORALE / CORSO INDIPENDENZA

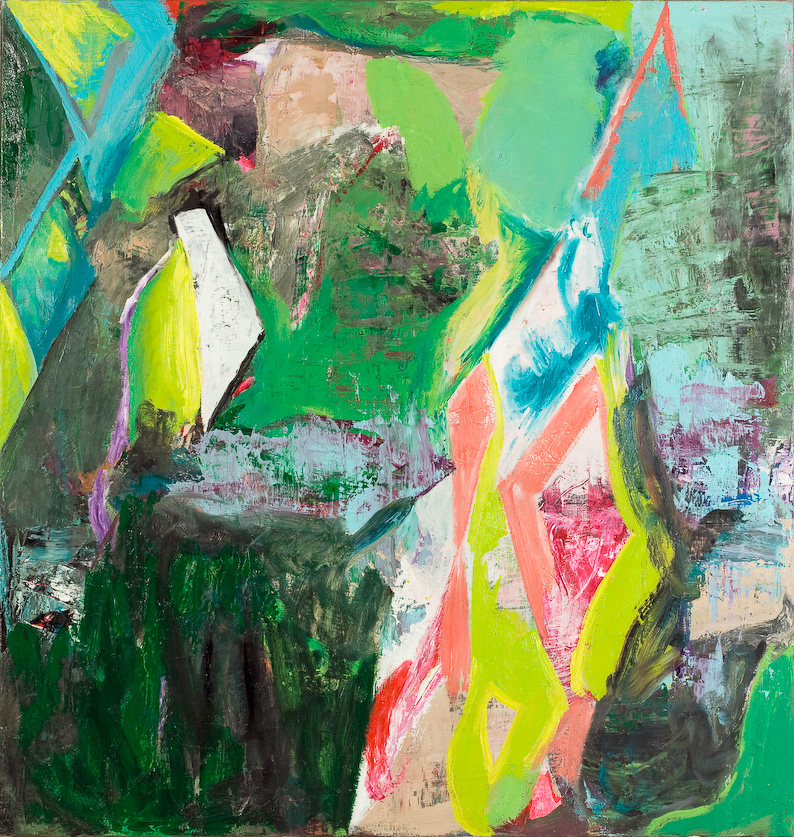

| Chor, 2006, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

Der Zyklus Pastorale (Corso Indipendenza) ist ein Weg auf dem Grat zwischen der Farbe und ihrer räumlichen Bedeutung. Wo das Bild sich der Betrachtung öffnet, da beginnt eine Figur, oft auch eine zweite zu erscheinen, während sich die Tiefe einer Landschaft bildet: Hügel, Wiesen, Ebenen, Plateaus. Kurz bevor sich das Erscheinen abschließt, kurz bevor der Raum fest angeordnet ist, kippt die Landschaft aber ab: Die Perspektive löst sich auf und die Bedeutung bricht, geht zurück in die Textur der Farbe, die sich ausspielt, ihre Leuchtkraft feiert – sie baut in ihrer Schönheit eine Spannung auf, aus der die räumliche Bedeutung wieder neu erscheint. Und wieder kippen wird.

Eine ähnliche Bewegung hin und her hat Richter früher in der Malerei gezeigt. Sie ist dort aber mühsam zu durchlaufen, da sie etwas Unerfülltes hinterlässt – eine Forderung, die offen bleiben muss und so den Betrachter vorwärts zieht in der Zeit. Richters Malerei bewegt sich parallel zu Lacans Analyse eines Begehrens, das immer wieder nicht sein Ziel erreicht, da es das Reale nie ganz ins Symbolische aufheben kann. Beide halten an der modernen Klage über eine zentrale Leere fest.

In diese Konstellation trägt Brunsmann eine minimale Drehung ein, die der Malerei einen ganz neuen Horizont eröffnet. Die Bewegung wird nun nicht mehr aus ihrem Ziel bestimmt, sondern aus ihrem Anfang, der das Versprechen in sich trägt, dass immer wieder etwas Neues für den Blick erscheint: Wenn aus der Farbe ein Bild hervorgeht, das sich auflöst und anders wieder aufgebaut wird, dann ist das nicht mehr die Bewegung, in der das Begehren immer wieder nicht sein Ziel erreicht. Es ist eine Bewegung, die den Blick im Versprechen seines Sehens trägt, ihm einen Aufenthalt gibt.

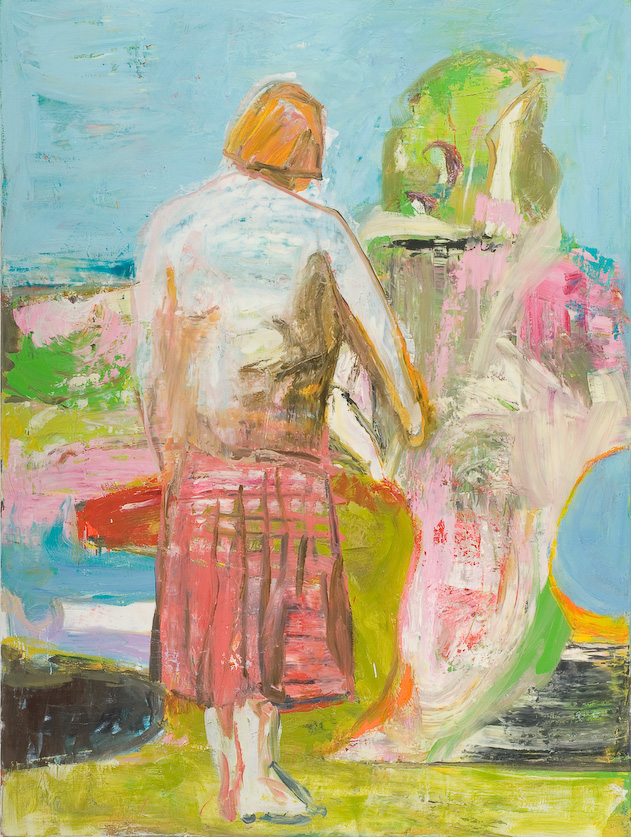

Das Motiv der Pastorale-Bilder ist die menschliche Gestalt in einer Landschaft, fast immer sind es zwei Figuren in einer Art von Austausch. Die erste ist ausformuliert, die zweite meistens angedeutet, sie changiert und kippt. In Erntedank ist die Figur, die im Vordergrund etwas aufhebt, klar konturiert, in Erinnerung an Millets Angelus und Die Kornleserin. Hinter ihr erscheint ein Hochplateau mit einem Baum, links begrenzt durch eine felsige Abbruchkante. Weiter hinten trägt ein Fluchtpunkt die Proportion der Landschaft. In dieser Perspektive müsste die andere Figur links an der Felswand stehen. Sie bildet sich aber anders heraus als erwartet, kommt nach vorne und kippt in einer atemberaubenden Bewegung die ganze Räumlichkeit des Bildes.

The Pastorale (Corso Indipendenza) cycle of paintings walks a fine line between colour and its spatial significance. Where the painting opens itself to the viewer a figure begins to appear, and often a second one as well, while the depths of a landscape form: hills, meadows, plains and plateaus. Just before the appearance is complete and shortly before the space can be firmly grasped, however, the landscape slips away. The perspective dissolves and the meaning breaks up, receding into the texture of the paint which parades about, celebrating its intensity – creating a tension within its beauty, out of which the spatial meaning appears once more, only to slip away again.

Richter presented a similar back and forth movement earlier in painting. There it is difficult to follow, however, because it leaves behind something unfulfilled – a demand that must remain open, thus drawing the viewer forwards in time. Richter’s painting has parallels with Lacan’s analysis of a desire that repeatedly fails to reach its goal, because it can never completely dissolve the real into the symbolic. Both adhere to the modern lament over a central vacuity.

Into this constellation Brunsmann adds a minimal twist, which opens a completely new perspective for the painting. The motion here is no longer determined by its goal, but rather by its beginning, which bears as a promise that something new for the viewing will always appear. If out of the paint a picture emerges that dissolves and then reappears in a different form, then this is no longer a motion in which desire repeatedly fails to reach its goal. It is a motion that sustains the gaze in the promise of seeing, giving it a short sojourn.

The Pastorale paintings’ thematic motif is the human form within landscape, and the paintings almost always contain two figures in some type of exchange. The first is clearly formulated, the second generally implied: it oscillates and shifts. In Erntedank (Thanksgiving) the figure standing out somewhat in the fore- ground, clearly contoured, is reminiscent of Millet’s Angelus and Gleaners. Behind this figure appears a high plateau with a tree, bordered on the left by a rugged escarpment. Far to the rear a vanishing point yields the landscape’s proportions. In this per- spective the other figure should be standing to the left against the rock face, but it forms itself differently than expected, coming forward and tilting the picture’s entire spatiality in a breathtaking motion.

* Stefan Winter in: DISTORTED MEMORIES OF NATURE, 2012

| Corso Indipendenza, 2007, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

| Ländliches Fest, 2006, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

| Erntedank, 2006, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

|

| Licht, 2007, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 180 cm |

|

| Die Nacht, 2007, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 230 cm |

|

| Geburt, 2007, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

| Frost, 2005, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 200 cm |

|

| Vogelscheuche, 2005, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 150 cm |

|

| Pastorale, 2006, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 150 cm |

|

| Versuchung, 2006, Öl auf Leinwand, 200 x 150 cm |

|

|

^ oben / top

|

|

|